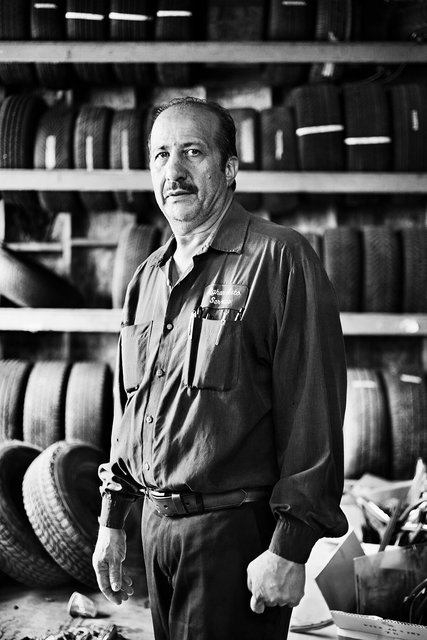

Nader and Waheed, 2017

Nader and Ahmed Waheed co-own Afghan Auto Service. Waheed started working in an auto shop in Kabul at the age of 11, when his uncle needed help, only agreeing to it if he would be allowed to drive the cars. Waheed’s mother wanted him to stay in school and attend university. He kept his promise, studying language and literature while running his own auto shop. After university Waheed began his military service, where he clashed with his commanding officer and was put in detention. Knowing he was to be sent to the front lines during the Soviet invasion led Waheed to escape Afghanistan through smugglers in 1983, at the age of 23. Waheed ended up staying with his friend Nader who had already left for India and was living in New Deli. Coming to Canada made sense for Waheed, as he already spoke English from university. Nader joined him afterwards. Once in Toronto they started Afghan Auto together with Mehmood, who has since passed away.

Nasrin, 2018

There was war in Nasrin’s country when she was 18 years old. The universities in her country were closed so there was no choice but to leave with a student visa in order to study physics. Nasrin lived through four years of physical safety, though with much uncertainty and fear of what to do at the end of university. With the country still at war, her fiancé applied to the UNHCR, where they were interviewed and accepted by Canada, arriving in 1988. Nasrin landed with two suitcases and $2000 hidden in her shoes, but without friends or family in Toronto. At first, Nasrin felt humiliated when she couldn’t communicate and understand little things, like how to shop. It was scary and lonely, and she felt like she was in a tunnel leading nowhere in the dark. She worried about how she would survive the first year and wished she could go back. During the end of the first year as a government sponsored refugee, Nasrin found a job in a coffee shop. A woman named Emily from Welcome House was a regular and told her “you don’t belong in this café.” She was the first person Nasrin disclosed her story to, also letting her know she was educated and spoke three languages. Emily helped her get her first job in a law office as a clerk where she started working with refugees from her country. During the war, blackouts were common due to bombing. This terrified Nasrin and added to the trauma of her losing her mother. Working with other refugees became Nasrin’s passion. She didn’t want anyone else to feel as helpless as she had. Thirty-five years later, Nasrin still has that passion to help refugees. Different People gave Nasrin opportunities over the years, like Jack, who encouraged her to work in a pilot project starting a refugee law office for Ontario Legal Aid. Nasrin often works with people without status in detention. It gives her great joy when clients win their cases, gaining liberty and a future in Canada. As a child, Nasrin dreamed of becoming a teacher and writer. Now she prepares refugees for their hearings by writing their real-life stories to help support their claims.

Loly

Loly is the executive director of FCJ Refugee Centre in Toronto, which she founded with her late husband Francisco. She hastily left El Salvador in 1990 with her two children when she was pregnant. Her family was in danger, as her husband was a human rights lawyer during the Salvadoran Civil War. The only country taking in Salvadoran refugees at that time was Canada. Loly found support and shelter when she arrived as a government assisted refugee. She realized that the unclaimed refugees arriving needed the same support and services her family received, and that they had the added emotional stress of not know their future status. Loly and Francisco approached the sisters from the Faithful Companion of Jesus (FCJ) religious congregation running the house for refugees where they were living, and the Sisters helped them open a home for women and children. Currently the FCJ Refugee Centre has three homes for refugees supporting up to 25 women and children, along with staff advising and supporting refugees recently arrived in Canada. Loly’s experience in Canada taught her that home is where the people you love and the people that love you are. She continues fighting for human rights and the rights of women, using many of the same skills she developed in El Salvador, where she worked for the human rights of children with Down syndrome as a physiotherapist. After the civil war ended the family returned to El Salvador for a few months in 1992, but it wasn’t home anymore. They wanted the children to grow up in a place not full of hate and violence, a place where they could be free to do what they want. Now she visits El Salvador with her grandchildren. Loly’s hope is to take their Salvadoran roots and Canadian ways to build a combination of the two cultures to make a better place.

Manivillie, 2017

Manivillie, a writer, poet and civil servant, lived in Nigeria when she was a young girl, as the country was recruiting people from Asia for work. The family had left behind her two teenage brothers in Sri Lanka to complete high school, preparing for university. By the time she was nine years old her father could see the situation changing in Nigeria, and they chose to go to Canada rather than the U.K. where they had family. Her father, a teacher, had many students who were doctors. They advised him to go to Canada, as The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto would be able to help Manivillie with her specialized medical needs. The Canadian officials even made the process quicker for the family to be accepted into Canada in 1987, when they realized they had enough points to immigrate instead of claiming refugee status. During the health screening, her mother was diagnosed with lung cancer. Manivillie says that this, along with her own health needs, would have been enough to deny them entry into Canada today. The family eventually found a home in Toronto at the Tamil Cooperative Homes, and Manivillie’s father established children’s Tamil language classes. Manivillie consequently felt a part of a community. Her mother’s best friend also stepped in to care for her and her sister after her mother passed. It took much more advocacy to bring her brothers to Canada. Her younger brother avoided being recruited to fight for the Tamils after paying a smuggler $10,000, but was detained in Switzerland the day their mother died. Her brother was only originally allowed to join the family in Canada to attend the Hindu ritual that a second-born son must execute for his mother upon her death. Manivillie has been an advocate for women’s rights, exposing the unspoken violence toward women in the Sri Lankan and South Asian communities, even developing health reforms in the eastern provinces of Sri Lanka with the government. Meeting and connecting to so many different people from a variety of cultures has made Manivillie feel she can be herself, being at home as both Canadian and Sri Lankan. No matter where she is physically, Canada feels like home to her.

Miklos, 2021

Honorable mention in the Segregation + Human Rights category - 19th Julia Margaret Cameron Award. The exhibition was at FotoNostrum Gallery in Barcelona on April 20, 2023.

Salam + Shogar, 2019

Salam used to work as a newspaper journalist and television presenter in Iraq. It was a very dangerous job. In 2006 he went to Iran where there was a Canadian Embassy and waited five years for an interview. Then the embassy was closed so Salam left for Syria in 2012 to obtain a visa, and the Canadian Embassy was closed down there too. Salam next went to Jordan and was then sent to Turkey. Eventually he came to Canada in 2014. It was a long hard journey, and he couldn’t go back to Iraq. While waiting in Iran Salam met his future wife Shogar who was working as a nurse in a small border town. The couple were separated while he sought refuge, as Iran didn’t accept refugees, Salam needed to find a safe country. They were only able to get married when Shogar came to Canada in 2016. It was better after that as he was not alone. When he arrived at his cousin’s place in Whitby, Salam didn’t speak English, so he found work at a factory. It was so difficult missing family and his Kurdish language. As his English improved, he worked at a gas station for two years on the night shift while going to high school. After graduating Salam attended the broadcasting program at Centennial College. Concerned about the language barrier for a job in journalism, he thought the technical areas might have more opportunities for him, and Shogar went back to school to study nursing. Salam, originally Muslim, isn’t religious anymore after living through killings in the name of religion. What he loves about Canada is that people of different nationalities, religions, and languages live together. Canada is his real home. Forty years ago, his uncle, a journalist, was arrested and executed by the government. His uncle’s fight for freedom became Salam’s, who believes that working in the media is a good place to fight.

Carolina 2017

Carolina originally worked in El Salvador as a journalist in independent community radio until her children's lives were threatened and the government tried to shut down the community radio stations. The children went to stay with their grandmother as it wasn’t safe. On September 11th, 2001, when they were going to meet her husband Oscar in Miami, Carolina’s daughter became ill. They watched the twin towers come down from a hospital television. By October 25th she met her husband Oscar in Miami as they had a visa for the United States and claimed refugee status there. The family wanted to go to Canada as they thought it was a safer place to raise their children, so they went to Vive La Casa in Buffalo to help them organize an appointment at the border. Canada took Carolina and her three children in as refugees in 2001 but refused her husband’s claim, due to his contact with the guerillas in his journalistic work, accusing him of terrorism. (He had interviewed people in the government and the guerillas.) By the time of Oscar’s hearing, the FLMN were an official political party in El Salvador. In 2014 after her husband received a positive decision for his application, he was called in for a final interview. He was told he was inadmissible and would be deported in a week. Many people were surprised when they first heard through the Toronto Star, about the campaign against her husband’s deportation. After much community activism, Carolina’s husband Oscar received his resident card in 2016. Currently Carolina is the Popular Education and Communication Coordinator at FCJ Refugee Centre. Her work at FCJ helps educate individuals going through the refugee process. She worked with community in El Salvador, and she continues to do so in Toronto.

Nader, 2017

Nader studied to be an engineer at Kabul University, meeting Waheed while driving by his auto shop near the university. Nader did his engineering practicum at Waheed’s garage in Kabul, and their journeys from Afghanistan led them both to Toronto where they co-own Afghan Auto Service. Many of the customers have been coming for decades, giving the garage a community feeling. Some Fridays they have a kebab lunch for whomever stops by, and friends getting their cars fixed often bring snacks to share during their visits. Although there are many clients originally from Afghanistan, people frequent from a variety of backgrounds. I have always felt the shop represents the best parts of Toronto and have enjoyed their hospitality many times while waiting to have my car serviced. The auto shop feels like a busy household where there is always time to ask how the family is. Along the walls of the garage are images from Afghanistan with a portrait I took of staff 20 ago while photographing for Toronto Life magazine. Nader and Waheed have been my mechanics ever since. Their garage is a gathering place where customers often enjoy conversation and food together. Spending time in their shop reminds me of my late father’s hardware business. The hospitality and eastern rhythm feels so familiar.

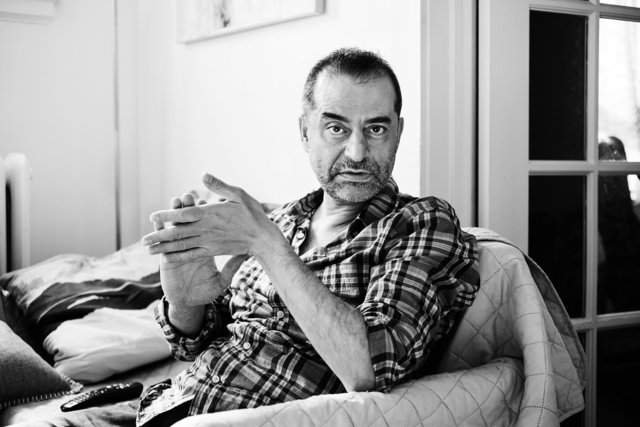

Omar, 2017

Omar is an artist living in Toronto. After the war in Iraq, he and others thought they could organize for a better future, but that didn’t happen, and he had to leave to save his life. Omar found refuge in Syria after finishing art college. It was difficult at first as he didn’t have skills outside of art to make a living. His art practice grew during this time. Syria is where he became an artist, even calling it a golden age for him. He didn’t feel like a refugee in Syria. Once the civil war started in Syria, Omar found himself again in danger, and in 2012 he was accepted into Canada through the United Nations. Omar lived in Canada apart from his large family until this past spring when his sister Roua and his two nephews joined him. Currently Omar is making art and mentoring Canadian youths through art workshops. He feels lucky to be in Toronto, a city where there are people living together with a mixture of religions and cultural backgrounds. This didn’t happen in the Middle East, and he conveys this possibility to his family living outside of Canada

Sashar, 2017

Sashar is a multi-disciplinary artist, who was born in Tehran into an immigrant family from the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan. The idea of being a migrant started with his grandmother as his mentor, who would sing and dance about past her life and homeland in her father’s house. Sashar’s grandmother taught him stories through songs, sighs, body language and dancing. When she died as the Revolution was happening, Sashar lost his headquarters. Post Revolution there was repression towards anything musical, including dance, and Sashar was imprisoned and tortured. After being hospitalized for the beatings he escaped to the mountains in Turkey. For the 12-hour journey Sashar was hidden in a 40-litre plastic container in an open top truck. The vehicle was searched often, and Sashar could only hear the sound and vibrations changing against the plastic container from the dark small space. After being dropped off Sashar had to walk to the other side of the mountain. There were hills upon hills. Every time the man taking him said “after this one,” then on top there would be another hill. Today that feeling of looking at the hills has become the engine that drives Sashar forward. Behind you is only the end. Sashar says exile happens in his own body and that is why he can be in exile everywhere. When he is at home in his body, mind, and emotions, it drives his dance, revisiting his experiences and creating moving memories. Arriving in Canada, him mom urged him to go to high school as he missed much of his youth. Immediately Sashar became the spokesperson of the race relations club though he barely spoke English. Soon after he started up the Eastern High School of Commerce multi-cultural arts society with a festival show. High school was the closest place to home. After graduating from engineering at Waterloo University Sashar became a dancer. He has worked more than 30 countries with his dance company Sashar Zarif Dance Theatre. As an artist Sashar feels the diversity of Toronto is a gift, initiating collaborations with different people creating new cultural perspectives.

Marilo, 2018

When Marilo was three months old the family left Chile because of the military dictatorship. Her father had worked as an agricultural engineer with the Allende government helping nationalize farms. After the coup on Sept. 11, 1973, he was arrested. As they lived in a small town where everyone knew each other, the police were put in charge instead of the military. The sergeant knew her father and let him go. From then they began their plan to leave the country. It took about a year to leave. Marilo was conceived on the night of her father’s release. She wrote a play about the family’s exile, meeting with her father once a week for two years to hear the stories of their journey. They arrived at the refugee hotel across from the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, and soon found an apartment in Etobicoke by the Old Mill where there was a large Chilean enclave. It was a good experience growing up in that environment, with lots of politics and food, even though they were poor and felt different from other children. There were difficulties having two identities. Marilo’s family had their suitcases packed and ready waiting to return to Chile after the dictatorship fell. When it happened in 1988, Marilo’s parents realized that it wouldn’t be fair to take the children from their home. Marilo’s work as an artist focuses on the concept of being in exile, on the idea of not knowing what your path is supposed to be. She is interested in how culture has been affected by revolutions, dictatorship, and colonization. Beginning as an actor she was angry with the stereotypical roles available, which led her to found a Latin American theatre company in Toronto. Currently Marilo is working on her PhD in Theatre & Performance Studies. Marilo believes art gives a voice to the issues that need to be talked about to make our world better. As a child Marilo never read a book of short stories about a child of exile. She wants to write that book.

Alejandra, 2017

Alejandra was born in Chile in 1968. Fearing persecution and death, her family escaped the military coup in 1973, settling in Vancouver. During the military coup anyone in Chile who was seen organizing groups could be arrested, tortured, and killed. This happened to her uncle who organized a soccer team at the bank where he worked. Alejandra’s grandmother risked her life by going and begging for his release; thankfully he was released the next day. Her uncle came to Canada as well but never recovered from that experience. Being part of an activist family, Alejandra experienced danger that few knew of in her Canadian life. From the age of 10 to 17 she went back and forth between Vancouver and South America, and between her parents, who had divorced. She lived in two very different realities. Growing up in Canada, Alejandra noticed people didn’t look like her and teachers couldn’t pronounce her name. She dreamed of being called Alexandra. She’s still regularly asked where she’s from even though Alejandra has a Canadian accent. The question makes her feel like she doesn’t belong. Alejandra never identified as a refugee. She says the media shows refugees in distress, but not later once they’ve settled into a new life. She simply strives to be happy and live a productive full life. She’s a fitness instructor, actor, writer, and photographer along with being a mom. We were in high school together where we shared a love of photography while co-editing the yearbook. I was unaware of her story until I asked on Facebook if anyone knew of refugees who would be interested to be part of this project.

Omar and His Nephews, 2021

Omar lived in Canada apart from his large family until this past spring when his sister Roua and his two nephews joined him in Toronto. They have enjoyed making art together.

Tom and Miklos, 2017

Soviet repression along with a lack of religious freedom led the family to leave Hungary in 1956. The brothers come to Canada as young children with their family because they had two aunts living in Montreal. Tom thinks it is a myth that someone grows up with the ambition to go to Canada or America, in reality they usually go where they already know someone, where there is support, or wherever their application is accepted. Tom the youngest brother developed as a visual artist later than his brothers, with their father being a musician they had a lot of cultural exposure. Starting in theatre provided low wages so he changed to software, eventually he was drawn to photography. Tom doesn’t quite feel Canadian or Hungary; thinking it takes a few generations to blend in. Tom is glad to be here, freer to think then when he lived in the United States. The brothers say with more rules in Hungary and repression of their feelings leading to less empathy, that they feel lucky their parents came to Canada.

Loly, 2017

Loly is the executive director of FCJ Refugee Centre in Toronto, which she founded with her late husband Francisco. She hastily left El Salvador in 1990 with her two children when she was pregnant. Her family was in danger, as her husband was a human rights lawyer during the Salvadoran Civil War. The only country taking in Salvadoran refugees at that time was Canada. Loly found support and shelter when she arrived as a government assisted refugee. She realized that the unclaimed refugees arriving needed the same support and services her family received, and that they had the added emotional stress of not know their future status. Loly and Francisco approached the sisters from the Faithful Companion of Jesus (FCJ) religious congregation running the house for refugees where they were living, and the Sisters helped them open a home for women and children. Currently the FCJ Refugee Centre has three homes for refugees supporting up to 25 women and children, along with staff advising and supporting refugees recently arrived in Canada. Loly’s experience in Canada taught her that home is where the people you love and the people that love you are. She continues fighting for human rights and the rights of women, using many of the same skills she developed in El Salvador, where she worked for the human rights of children with Down syndrome as a physiotherapist. After the civil war ended the family returned to El Salvador for a few months in 1992, but it wasn’t home anymore. They wanted the children to grow up in a place not full of hate and violence, a place where they could be free to do what they want. Now she visits El Salvador with her grandchildren. Loly’s hope is to take their Salvadoran roots and Canadian ways to build a combination of the two cultures to make a better place.

Visual Arts Mid Career Project Grant 2017

I would like to thank the Ontario Arts Council for supporting my documentary project "After Refuge". I would also like to thank the people that shared their stories and resiliency with me. This body of work is dedicated to them and my father who have made a better world. I have also been warmly supported by my friends and family during the five years leading up to this exhibition, the love and support has fueled me during this creative project. I want to acknowledge Jennifer Long and her insightful photo editing skills, and Kate Barker an amazing word wonder who has helped edit the stories. My husband Peter listened to my concerns and ideas, and was also an expert exhibition installer.

Carolina's Journey, 2017